From Pentecost 2021 to Pentecost 2022, I have undertaken a Franciscan tour of reactions to secular modernity. Beginning with the feast of the Mother of the Church I am offering a Tribute to Fr. Peter Damian Fehlner, OFM Conv. by carrying forward what he opened up and had not yet fully articulated…

_________________________

Mother of God – Mother of the Church

Mother of God – Mother of the Church

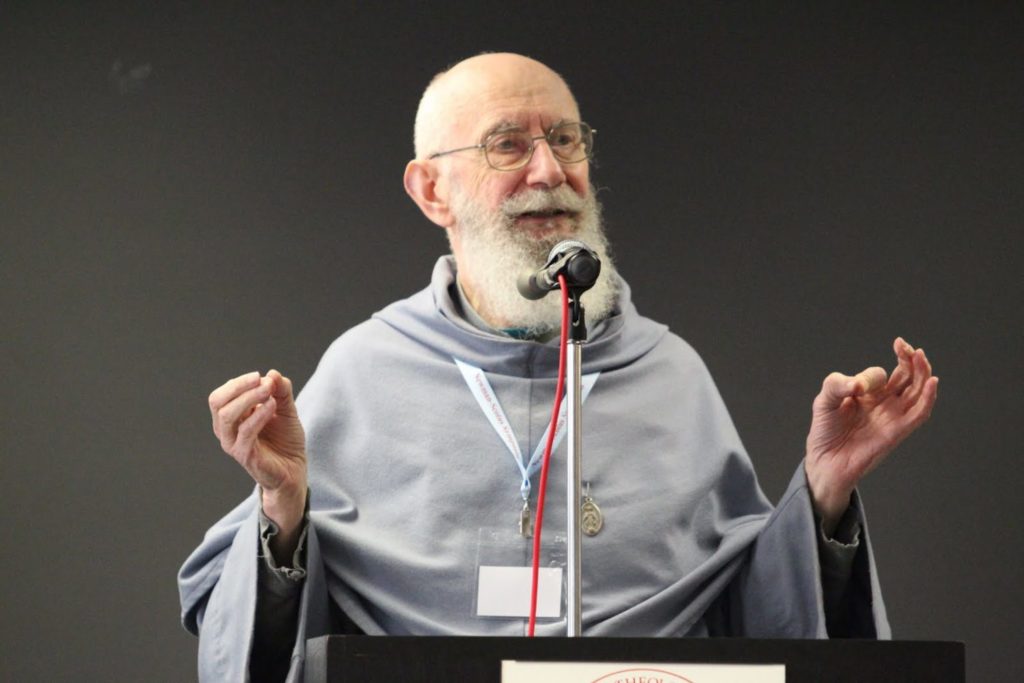

A Tribute to Fr. Peter Damian Fehlner, OFM Conv. 20 July 1931 – 8 May 2018

In the third century we find references to Theotokos, Mother of God in prayer, but it took until 431 at the Council of Ephesus to define irrevocably Theotokos, Mother of God. In November 1964, as the history-making teaching on the mystery of the Church, Lumen Gentium,[1]was being approved by the Council Fathers, Pope Saint Paul VI solemnly proclaimed Mary as Mother of the Church. On 11 February 2018, Pope Francis issued a decree for the Memorial of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Mother of the Church, to be celebrated each year on the day after Pentecost. This reflection is on Mary’s Motherhood in a Scotistic key.

First, I honor my teacher, Fr. Fehlner, by carrying forward what he opened up and had not yet fully articulated. Fr. Fehlner taught the language of the Scotistic tradition as a gift and handed it on with the Franciscan tradition that the friars have for developing and elucidating what Bl. John Duns Scotus intended as we take stock of who we are as Church in modernity.

Second, in the exchange of gifts between Jesus and Mary, logically, that one who gives is active and one who receives is passive. “Jesus is active in giving divine grace to his Mother, and is passive in receiving human nature from her; Mary is passive in receiving grace from Jesus (that makes her full of grace), she is active in giving him (perfect) human nature.”[2] Mary as predestined with Christ is a grace conferred on her by her Son, not independently of Him.

Third, according to Duns Scotus, Mary’s maternity, her activity in her Son’s conception, is active, not just a passive principle in the conception and formation of Jesus’ body. Mary is an active principle! Duns Scotus’ thesis of Mary’s natural fecundity was absolutely new and drawn from Galen, a physician. The other theologians of his day aligned with Aristotle, who taught that the father alone was the active principle, while the mother had a purely passive role, offering the material for the formation of a body. The father’s seed alone possessed active power.[3]

Duns Scotus’ firm defense of the woman’s active role in the procreation of offspring is more important than ever in the debate over the sacredness of life and, to many, the overreach of the United States Supreme Court in Roe v. Wade. If the Court’s decision is to return jurisdiction to individual states, Duns Scotus’ defense of woman as an active principle remains. The Court makes civil law; the Church, the law of God. “The truth cannot impose itself except by virtue of its own truth, as it makes its entrance into the mind at once quietly and with power.”[4]

Duns Scotus thought as taught by Fr. Fehlner builds upon St. Francis of Assisi and St. Bonaventure. Historically, they are in pre-modernity, and Fr. Fehlner recognized why retrieval of their thought was necessary for modernity. Friars and laity who studied with him witnessed a critical and analytical sense that may not have been appreciated at the time, but has everything to do with the evacuation of doctrines and practices effected by our secular modern age and the drift of the Church towards the secular. Retrieval of the thought of the Franciscan masters is necessary. Vatican II paused to ponder: Who are we? What are we about?

Hitting the pause button is often necessary because the Church, historically, is always in crisis. Candor about the impact of evacuation of doctrines and practices in secular modernity and the drift of the Church towards the secular are needed more than ever. Since he died on 8 May 2018, I realize my duty to cultivate the gifts Fr. Fehlner has left, to plumb deeper, to lead others to critically engage, and to go beyond our discoveries and contributions. In line with the subtle thought of Duns Scotus, Fr. Fehlner discovered Duns Scotus and Newman in Dialogue.[5]

Fr. Fehlner claims Duns Scotus’ Prologue to his Ordinatio to be the most subtle and systematic introduction to dogmatic-systematic theology ever written. The issues for that period of theology have been clearly identified and magisterially expounded. Fr. Fehlner lamented that our times fail to cultivate dogmatic theology, allowing instead for the substitutions of ways of thought other than the metaphysical as the primary instrument of the revelation and study of salvation history. He observed that thinking dogmatically and systematically in theology has seriously decayed. How many view Duns Scotus as one who prophetically anticipated and resolved decisive questions of a “critical” theology that emerged after he died? Duns Scotus anticipated the solution, not the errors of a Franciscan, William of Ockham, and their progression in Luther and Hegel.[6] With the dawn of modernity, Ockham’s errors began to replace and become the fashionable mode of thinking about the divine and about history.

First, Duns Scotus identified the Ockhamist problem of substituting nominalism as a metaphysician logician before it burst on the theological scene. Second, Fr. Fehlner discovered commonalities between Duns Scotus and John Henry Newman. Third, Fr. Fehlner’s genealogical thinking passes through the Greek and Latin Fathers, Augustine and his interpretation as it passes through Anselm, the Victorines, Bonaventure to Duns Scotus and Maximilian Kolbe. He lauds and retrieves the definitive form of the insights in theology and philosophy, East and West, into the structure and content of the term used by Duns Scotus, “our theology,” associated with the work and spirituality of the Poverello of Assisi.

Fr. Fehlner retrieves this “Franciscan thesis,” or opinio minorum, which revolves about the absolute primacy of Jesus Christ or the question of the primary motive of the Incarnation, and about the mystery of the Immaculate Conception or the question of the preservative redemption of Mary and of her joint predestination with Jesus. Duns Scotus does not speak of Mary’s predestination, but his immediate disciples[7] and other friars taught the uniqueness of Mary’s predestination with Christ. To have been so predestined is a grace conferred on her by her Son, not independently of him. The question still debated is: Did Duns Scotus actually teach this? Did Bl. Pius IX and his successors refer directly to the scotistic school or to what Duns Scotus expressly taught? Fr. Fehlner is clear that Duns Scotus taught the predestination of the elect, including Mary, in Christ antecedently to any prevision of sin.

Fr. Fehlner defends the vocabulary of Duns Scotus as vivifying for its exactness i.e. that all of creation is good. Fr. Fehlner sets the right tonality about Duns Scotus: the Franciscan motive of creation aligns with the original plan for Christ to be born even before the fall of Adam. He and the friars who understand the Scotistic motive of the Incarnation prefer the Franciscan School while being open to all Christian and Non-Christian religions. In future entries I will bring forth insights that unlock Duns Scotus when theologizing and Fr. Fehlner for secular modernity.

Fr. Edward J. Ondrako, OFM Conv., Tribute to Fr. P. D. Fehlner, eondrako@alumni.nd.edu

__________________________________________

[1] At Vatican II, the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, Lumen Gentium.

[2] R. Rosini, trans. P.D. Fehlner, Mariology of John Duns Scotus (New Bedford,MA: Academy of the Immaculate, 2008), 26.

[3] Rosini, 26-27. See fn. 48 re Bonaventure, Thomas Aquinas, Richard of Middleton, and Giles of Rome.

[4] Dignitatis Humanae, The Declaration on Religious Freedom, 7 December 1965, no. 1. The best way to understand this is via Newman on development of doctrine. In 1973 I was with the New York State Catholic Conference where the senior attorney opined that Roe would be overturned within 10 years.

[5] P. D. Fehlner, “Scotus and Newman in Dialogue,” in The Newman-Scotus Reader, ed. E. Ondrako (New Bedford, MA: Academy of the Immaculate, 2015, rpt. Canonization issue, 2019), chapter 7.

[6] I will return to Duns Scotus anticipating the solution, not the errors of Ockham, Luther and Hegel.

[7] Beginning with Bartholomew of Pisa, St. Bernardine of Siena, and later Vulpes and Moral.

Fr. Edward J. Ondrako, OFM Conventual

Research Fellow Pontifical Faculty of St. Bonaventure, Rome

Visiting Scholar, McGrath Institute for Church Life

University of Notre Dame

June 6, 2022